|

|

Interview with

Eugène Godfried: Interview with

Eugène Godfried:

Call for dialog on the 1912 Massacre

October 5, 2007

Andy Petit: How did your interest in the 1912 Massacre of

over 7,000 AfroCubans start?

Eugène Godfried: In 1981, for the first time, really, I was confronted with people talking about the race situation in Cuba and the differences between Havana and Santiago. Havana was being run by euro-iberian-spanish ideas and

views, views that were looking up to the North in terms of culture. Santiago was seen as the

"tierra de los negros," in a belittling way.

Andy Petit: How were you confronted?

Eugène Godfried: I was in Granada, invited by Prime Minister Maurice Bishop, with a small delegation from Curacao, and while I was there, a ship, the XX Aniversario, came in from Carifesta in Barbados and docked at St Georges, the capital. On board there were over 200 artists, and they performed for the Cuban workers building the airport and also for the Grenada public. During those days, I was also in contact with the Cuban embassy through its political secretary Gaston Diaz and Ambassador Rizo. They included me in all the programming and introduced me to the artists, including Pedro Izquierdo -

"Pello el Afrokan" - who became a good friend. These artists emphasized the Caribbean, the African component of Cuban culture. All of them hinted to me about 1912 but no one went in depth into it. First I had to understand the general situation of Africans in Cuba. Eduardo Rivero Walker spoke about the English-speaking immigrants in Cuba. Electo Silva, director of Orfeon, spoke Creole, had lived in Haiti, and gave me a different perspective on Cuban life. I also got to know Eliades Ochoa and Alberto

Lescay, among others.

Silva and Lescay told me that because I was going to Havana, I was not getting the real picture of what Cuba was like. They told me I needed to go to Oriente, the most Caribbean tinted area in Cuba and the source of all its liberation movements.

I then coordinated a visit for this ship to Curacao with Prime Minister Don Martina. Because of Cold War politics, they were only allowed to come to a dry dock. At first the artists were not allowed on shore. Then the PM and his Lieutenant, Governor Ornelio Kees Martina, allowed them to perform on the boat and also to come on shore as tourists. I turned the whole ship into a theatre. It nearly cost The Prime Minister his job.

Andy Petit: How did you come to start researching 1912?

Eugène Godfried: It was maybe my 3rd or 4th visit to Cuba, I came as a guest of the Union de Jovenes Communistas in the early 80's. They took us to visit the sites in Havana, and one of them was the Museo de la Revolucion. I noticed a large color photo there of a group of black Cubans. When I asked the guide who that was, she said, "that was the leadership of the Independientes de Color, a party of blacks, but they did not last long." The way she responded made me feel that something about the topic was taboo. Right there I was hooked and wanted to find out more.

Leadership of the PIC

I heard a little more about the Party in Havana in conversations, I was told the subject was taboo, and that Marti said "Cubano es más que blanco, más que mulato, más que negro." Therefore any discussion of 1912 was counterproductive.

My most important early source was a Black Panther in exile in Cuba after hijacking a plane in Arizona, Michael Finney. He told me of the existence of that black party and that they were banned, and that there was a whole turmoil around it in Oriente. He got this from his wife who was from Guantanamo.

I continued myself again to find out more and to find out how it was that Cuba had had a black party. I found out there was a serious colored problem in those days.

Marcus Mosiah Garvey himself visited Cuba in 1921 to inform himself about the discrimination there. His UNIA in Cuba was the 2nd largest chapter after the US, both of them ahead of Jamaica.

I also found out that many people were killed, there was even a hunting of Haitians and Jamaicans in 1912.

|

|

Eduardo

Rosillo

|

I took my next steps thanks to Eduardo Rosillo Heredia, who was in Havana in 1990 and was the

only person there who really talked about this topic. He was from la Maya, and he told me they called it "una guerrita de raza," a little race war. He explained that the bourgeoisie did not like the party and that many of the people were killed in la Maya, no less than 3,000 dead. Even the hunting went way outside in the bush where no one could see, so more were killed than that.

Rosillo told me that to get a better view of the entire situation on race before and after 1912, I should go to Santiago and especially Guantanamo. Since I was also interested in musicology, he told me I could find out there about the birth of the son, especially in Guantamo where there was a high presence of immigration from the Caribbean. All the islands have played a role in the development of Cuba, its culture and its struggles. He also advised me to look into the roots of son in the Changui.

A few years passed by, and in 93 I went to Santiago on the invitation of the president of festival Bolero de Oro, Rodulfo Vaillant, to broadcast the festival live. I was with Rosillo, seconding him as animator. I had the opportunity to talk further on 1912 -- Rosillo and others took me to la Maya. Of course, I knew the song,

"Alto Songo, se quema la Maya." We used to dance to it a lot in

Curaçao, when I had no idea what it meant. Rosillo told me that it had to do with 1912 - there were two villages, Alto Songo on the hill, then lower in the valley, la Maya. They took me to see both villages and to talk to the people. My greatest surprise was that it looked like I landed in the middle of the Congo. The youths did not know much, but the older people knew more, they had the roots opinions. At first, they were hesitant to talk, but once they started they did not want to stop. They stressed the importance of

Antonio Maceo and disagreed with how officials stressed Marti's importance, how they characterized Maceo as

a tough man, a soldier, and not as the inspired leader he was.

UNEAC Santiago & la Maya, Poder Popular, and the local bureau of the Central Committee all told me they wanted me to come back and work on this further, that I would receive all collaboration I wanted. They had a need for further study of these disturbing events. There had been a lot of emphasis placed on the fire in la Maya and the looting. This had been used to blame the inhabitant, to blame the victims.

Andy Petit: You mean like in New Orleans?

Eugène Godfried: Yes! And even up to now, it is a pre-occupation. I told them that is a good preoccupation and that I would help them change the face of this reality.

I got back to Havana, read and talked to people. Official sources told me about the

Societies of Color -- I found out this was their term, not the term used by black Cubans, who called them by their name: Club Athena, Buena Vista Social Club, and so on.

At the Festival Bolero de Oro, Rosillo put me in touch with the Director of the Provincial Section of the Ministry of Culture in Guantanamo, Carmen LaMoru La'o. She invited me officially to come to Guantanamo and collaborate with their office in order to do research on the cultural identity of Guantanamo, its Caribbean nature, the African, the Indigenous

there and their relationship with the Caribbean.

She put me in touch with many of the historians I worked with in Guantanamo --

Joel Mourlot, Ricardo

Riquenes, and others like them. The Union de Periodistas de Cuba in Santiago, especially the president, Julia Cleger Barthú, who is a member of the bureau of the Communist Party in Santiago, and Josefa Melian Savignon, also helped me contact the historians.

The Communist Party in la Maya, the Comite Central, suggested Maria Eliaz, as did Rodulfo. People told me she was the most informed, the most passionate. After I did some fact finding I went to talk with her. I later

published an interview with her.

Andy Petit: How did these historians treat the topic of 1912?

Eugène Godfried: All treated it with a very high level of seriousness. They were very happy I was doing this

work as there was lots to clarify. First the idea that the Independientes were

a racist party has to be destroyed, it is false, they were not.

When Estenoz, who had been a general in the Mambi Army, captured soldiers from the regular army and from the

Batallón de Voluntarios - he ordered that they be treated with care, he forbad any mistreatment.

So did Pedro Ivonet, Eugene Lacoste, and the other founding members of the

party. Pedro Ivonet and Eugene Lacoste both spoke French and Creole

as well as Spanish. It was a humanistic party which had the most socially developed program available in Cuba to that point. The historians wanted to have clarified that the party had very broad support across Oriente. Whenever he or the party visited far away areas such Yateras, Maracaibo, or Romelier, huge amounts of enthusiastic people rallied around them.

The Independientes campaigned against the Ley Morua, its derogation or suspension. They did not rob, they did not burn. It was the euro-iberian-spanish business people who burned la

Maya to show people in a bad light. It was an easy way to obtain the insurance as an indemnification for their losses.

|

|

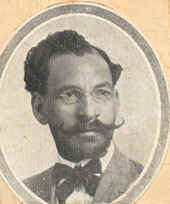

Pedro Ivonet,

a founder of the PIC

© 2007 Bohemia |

As long as this is not cleared up, the people of la Maya will continue to suffer the consequences. People,

even officials, view the Blacks of la Maya as aggressive, willing to burn and loot, and therefore they have to fear them and keep an eye on them. The euro-iberian-spanish think that way, since the number of black people is large, la Maya is densely populated, it makes them nervous, and they think they have to be careful, as these people are aggressive. This was false propaganda made in 1912 by the media of the elite to justify the criminal acts of the government of Jose Miguel Gomez and it is still around today.

Andy Petit: How did people explain the difference between Havana and Oriente on 1912?

Eugène Godfried: In Havana there is a general neglect and denial of this topic. Talking about issues of people of color is taboo in Havana, not so in Oriente - there they have a burning need to have this matter better known.

Then there is a statement by the president of Casa de las Americas, that Cuba is Latin American, meaning euro-iberian-spanish.

In talks with Party officials, I came to understand that the official figures - 70%-80% white, 20-30% mulato, negro - are a serious mistake. Right in Havana that is not true. In Oriente that is not true. In Matanzas it is not true. There are areas where intentionally the Spanish brought people from the Canary island and Spain to work in Pinar del Rio, in the tobacco areas. It was for the

blanqueamiento (whitening), this is even stated in several encyclopedias.

On a national scale, the authorities and official institutions use these percentages to organize the

society in all sectors. In the professional schools, the majority of students and professors are always

euro-ibero-spanish. For officials, in all spheres of life, you will have an absolute majority of euro and a minority of the Africans, even in Oriente. Oriente then becomes less important as a whole, Havana more important, and that is an unhealthy situation. Everyone in Santiago and Guantanamo who is conscious knows this.

The censuses have been carried out by people who have no training in cultural

anthropology whatsoever.

Oriente people are struggling for more recognition, they want to be associated with the Caribbean, they want the Caribbean to know more of them. This is a sign that they are very conscious of the teachings of Antonio Maceo, who said that there is no need at all to have anything to do with the euro-anglo-saxon elite. We can do it ourselves, form one nation with our brothers and sisters of Haiti, Santo Domingo, and Puerto Rico. This idea is absolutely lively with people of Oriente, more than anywhere else in Cuba.

I was once asked by a former director of Radio Havana Cuba, "What is the importance of Guantanamo to Cuba? What was I going to do there?" This shows a complete bankruptcy in her on these matters.

Each stage of every national revolt was initiated in Oriente, not otherwise. When officials who were euro-ibero-spanish saw that the protests by the Partido de los Independientes de Color were

1) initiated by people of color, 2) so strong in Oriente, they knew they had no control over Oriente, they had to smash this Party.

Years later, the Partido Socilista Popular, the predecessor to the current Communist Party, at one point contemplated the need to split Cuba into two because the color problem had proved so difficult to solve. This party used to rally many Africans, they had the only radio station open to the rumba and son, Radio Mil Diez.

Now you have to think of all of Cuba. Matanzas, Sagua la Grande, Villa Clara, Havana, the city and the province, even Pinar del Rio, Guines, all those areas. We need to call for unity, as the problem should be dealt with on a national basis.

These elements are essential for studying the Partido Independientes de Color further. I had to study thoroughly the history of the son complex, why has it practically dissappeared. When I asked officials about this, they would say, "Eugenio, a ti te gusta la musica de negros, Cuba no es asi." You can imagine my reaction.

Why is it that Arsenio Rodriguez sings about el Club Social de Buenavista? I found out that in the official jargon, this was a Sociedad de Color. What happened to all those, to the Africans? Why is it that in front of me, they would say "Tu no eres africano, tu eres cubano" to a Cuban of African descent?

Andy Petit: what did happen?

Eugène Godfried: These societies have been in existence since the 19th century. Remember that Jose Marti had sent

Juan Gualberto Gomez who was with these societies -- they had already formed the Directorio Nacional -- to mobilize their membership to support el Partido Revolucionario Cubano

- Marti's party - and Independence. After Independence, they continued as a form of shelter for the Cubans of African descent, providing education for their members and children.

They were also the meeting points to insure the continuity of the cultural manifestations for this social category. For example, the new generations and members were taught to play and dance to the son rhythm complex and the rumba. Traditional culinary arts were being taught and held high. Sports & recreational activities were being looked after -- baseball, soccer even cricket. And these societies were breeding ground for political ideas. Even up to the revolutionary period that preceded 1959,

the one that started in 1953. On the first of January, 1959, with the triumph of the revolution, the first speech delivered by Fidel Castro Ruz -- according to the UNJC, the Union Nacional de Juristas de Cuba --

he discussed all of those social clubs and abolished them by desegregating

them. I have persistently looked all through the decrees and laws in which these clubs might have been abolished and there is no such decree or law that states that. So I concluded this was a mere political decision.

Andy Petit: Which could be reversed?

Eugène Godfried: Yes of course, which could and ought to be reversed because the members of the former clubs told me, they were left with nothing overnight, they had to deliver the keys in the morning as the buildings were nationalized and the decision was taken to stop their existence.

I had to study this whole phenomenon of the African presence, its relationship to ruling forces, to take this seriously and try to rectify the errors.

It is in this framework that I have studied the phenomena of the African presence and 1912. In order to understand better, I have had to analyze all the massacres.

Aponte, Placido in 1844, la Protesta de Baragua, and 1912 itself.

Andy Petit: What do you see happening on this issue in the near future?

Eugène Godfried: First of all we need Fidel Castro Ruz to take action in this regards while he is still alive so whoever follows cannot come with any excuses or delays. The African people of Cuba remember Maceo. Their confidence lies with Fidel Castro Ruz, they have some confidence as he has been able to keep peace and tranquility regarding race relations and he has protected them quite a lot.

He himself is not totally free because he is surrounded by elements who inherit a legacy of old societies, with all the prejudices that old system entails. Some even think that the leader of the Revolution is encircled and censored by these elements and it is not to their convenience that he take the measures he wants to take.

Andy Petit: And if he does not take action?

Eugène Godfried: Great difficulties, a total disgust and removal of support by people of African descent from the process. We should always avoid another blood bath in Cuba. I have not put

all this out before, but the time is right for this, to call for serious dialog, for world community attention and support.

All solutions must come from within the island itself. No outside interference is allowed. Those who historically have rested on the imperialist circles in the United States and elsewhere are completely acting against the spirit of warnings that Antonio Maceo has taught us in the past. Therefore, all terrorist actions are severely condemned as well as plane bombings. I used to travel a lot with Cubana de Aviacion from Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, and Jamaica into Havana, back and forth. I could have easily been a victim too of the bomb blast of 1976.

We could also see an official condemnation, posthumous, of President Jose Miguel Gomez

and all who were involved in executing this massacre in 1912, including

the Batallón de Voluntarios, who can only be compared to the Ku Klux

Klan.

Last but not least, seeking freedom for the 5 imprisoned in the USA is a must in the line of ending outside interference without the least possibility of having the old forces responsible for racial discrimination and massacres in Cuba return to power. Never again should we have slavery in the Caribbean or any part of the world.

Looking at the events that preceeded the 1912 racist massacres, it was all about a call or demand of the PIC leadership to derogate the Morua amendment and other laws that were adopted the 14th of February, 1910. Martin Morua Delgado himself died in that same year, a few months later. The demand to derogate that amendment continued persistently and the response given by Jose Miguel Gomez was slaughter by the regular army and by the

Batallón de Voluntarios, nationwide, with a strong emphasis on the eastern part of Cuba, from la Maya up to Guantanamo. The American army, as Fidel Castro pointed in the article in Granma on August 16, indeed came out of the Guantanamo and patrolled the entire province of Oriente up until Camaguey. There is no evidence that they shot anybody. But it must emphatically be said, as Fidel Castro points out, that the secretary of State of the Republic of Cuba, Manuel Sanguily, had arranged with the US government to place their naval base in Guantanamo instead of extending the charcoal production they had under way in Bahia Onda, which is located on the northwestern part of the island. Bahia Onda belonged then to Pinar del Rio and now to the province of Havana, and was an area where most of the population consists of immigrants from the Canary Island and Spain,

who were therefore light skinned. Bahia Onda was an area devoted to tobacco and sugar cane production.

We remind Fidel Castro and everyone else that it is no surprise that Sanguily took this proposal to the US as he was well known for his racist attitudes and expressions. He was the representative of the euro-iberian-spanish elite who had taken over after Independence a few years earlier in 1898. The social category that he represented was segregationist and racist and collaborated with the segregationist and racist US government to take over Cuba. It is therefore understandable that Sanguily chose Guantanamo

to place the US naval base, as it was the region of the maroons and the palenques, where Guillermon Moncada put an end to the rancheadores, the slave hunter elites led by Miguel Perez, uncle of Pedro Agustin Perez. Guantanamo was the land of

Mariana Grajales and Antonio

Maceo, the land with the highest representation of African descendants and indigenous people. And we won't forget that Guantanamo is so close to Haiti with its revolutionary history, and to Jamaica. As a consequence till today the entire Caribbean region is a victim of these actions. We ask again Fidel Castro Ruz, comrade and colleague, to include these facts in his reflections and to proceed to immediate action, just like Antonio Maceo would have done by combining theory and practice. Even when Maceo was ill with 26 wounds on his body, he would jump on a horse, take his cutlass, and go to defend his cause of peace, equality, social progress, and anti-racism, which was his major preoccupation. We consider Fidel Castro to be a continuation of Antonio Maceo more than

he is of anyone else.

|