|

Dialogue

with Founding Leaders of Guantanamo’s Social Club Dialogue

with Founding Leaders of Guantanamo’s Social Club

‘La Nueva Era’

by Eugène

Godfried

Caribbean specialist / radiojournalist

Community organizer

Radio Havana Cuba

Radio CMKS - Guantánamo

All Photos in this article

© 2004 Luis Bennett Robinson

<== FORMER SEAT OF “LA NUEVA ERA”

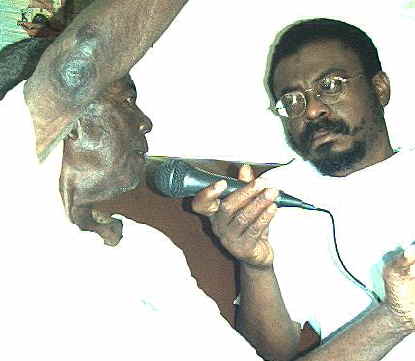

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO ==>

PAST PRESIDENT

SOCIEDAD ‘LA NUEVA ERA’

GUANTANAMO

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Let us start our dialogue with our guest Luis Mariano Durruty Nolasco, thank you for accepting our invitation.

Cuba is a musical powerhouse, but much of the developments leading to that fact took place in the ‘Sociedades de Negros’, the ‘Societies of Blacks’, in the initial decades of the twentieth century. It seems to me that you have some experience with those Sociedades de Negros. What can you tell us about that?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Yes, of course. Taking into account my age, and also I had the opportunity of having my father who was a profound lover of the affairs of those societies and was a founder of many of them. Among them the club Aponte in Santiago de Cuba, and in Guantámo he was with the societies Moncada and La Nueva Era. Those were societies of people of color, one can say that were better known as societies of blacks.

So, at an early stage of my life, I liked them and was attached to those circles, and I had the opportunity also to share with others in those first organized societies. As a youngster I used to go with my father to those societies, he took me with him. And, as I started to grow and mature, as Mariana Grajales would say [Antonio Maceo’s mother], I became a youth leader in the Societies. That was during the years 1938 and 1939 in Club Aponte of Santiago de Cuba. Afterwards I moved to Guantánamo, because I was born here, and I became a man in Santiago the Cuba and Guantánamo. So, once here I got involved in the societies Moncada and La Nueva Era. I became the Secretary and also President of La Nueva Era. I also collaborated for a long time with Club Moncada. Anyhow, I continued to develop myself in that ambiance. In those times there existed several societies, especially in Guantánamo. You had among them the ‘sociedades de blancos’, societies of whites, ‘sociedades de color’, societies of colored people, as I said [smiling].

Among the societies of coloreds, you had the Club Moncada and La Nueva Era.

Moncada was for the people who were better off, the professionals, people who had work that could allow them to more or less respond to their needs.

La Nueva Era was for the youth who liked to dance and enjoy the scene.

The same thing happened with the ‘Sociedad de los “Mulatos”, the society of mulatoes, who also had their clubs.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Which ones were those?

LUIS DURUTTY NOLASCO

“EL SIGLO XX”, which had the same characteristics. The same characteristics from the point of view that their members too came together for their recreation. Their charges were a little more expensive. Things like that.

Then there were also the ‘sociedades de blancos,’ the societies of the whites: “La Colonia”, “Viejo Catalán”, “Union Club”. Those were the white societies, that were also active in the same way, Those societies whose members were able to financially cooperate more determined a higher standard, or otherwise its successive descent in level that characterized the rest of their societies. [???]

Such was the environment that existed for a long time here in Guantánamo, and I, logically, as was usual for that epoch, was active in the society La Nueva Era. Of course, according to my possibilities that was the society in which I developed myself. There is where I had the opportunity to become the President as well as Secretary on many occasions, and in that way I was able to develop myself further.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Fine, you told me that your father was the founder of the society Aponte in the city of Santiago de Cuba, and also of many other ‘sociedades de Negros’. What was your father’s name?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Ambrosio Durruty Durruty.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Precisely, let us get back to the societies of which you yourself were the leader and had the honor of being the President and Secretary, like La Nueva Era and Moncada. What was the importance that those organizations had for people of African descent, say blacks, say coloreds, seen in that epoch.

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

They played a role that for those times, I should say, was of the first order. Because, according to the possibilities that existed then, they could develop themselves. The successive government authorities, when there was an occasion and there was one or another major event, immediately rushed to extend invitations to those ‘societies of color’ as they were termed then, so they could participate. With the intention to dress up the surrounding. At the end of it all they were the ones who had the control over everything, but anyway whenever there was a presentation, they always tried to make sure that the Board of the societies of people of color were present. Discourses and those things were held. That was the environment then.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

When you say the government authorities, do you mean the politicians of the country?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

The politicians of that epoch.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

That means to say that they had to recognize, respect, or at least take into account the societies of people of color?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Completely, completely, because, moreover, they used them also for their election campaigns. They made use of those means too. It was of fundamental importance, and that’s why they always took the societies into account.

When a visitor of importance arrived, they rushed to the societies to announce it by saying, “listen, on such and such a date you have to be present there and there…” That was the fundamental method that they used for that. On such a day all the representatives of the societies would be present. Whites, mulattos, blacks, in order to demonstrate that there was unity in the overall society. That’s how the development was, especially in our small place.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Speaking about the societies, besides the dance activities that they organized, and I also understand that they fulfilled a wider social functions, ceremonial ones, like when they had to represent the country. Now, what other activities did they hold. For example, sports?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Yes, here mainly, sports. In the societies where I was active, we played a lot of sports. Inclusively, there was a friend who was almost a relique[???], he had a baseball team. His name was Máximo Lopez. His team was called Máximo. Almost all of his team – members were members of the societies. He did well. After the triumph he went to Havana and after that I never saw him again.

Other activities that we did a lot were: cultural activities, tombola, poetry. There were members who were more educated, and who always tried to keep the cultural level high. We had a member by the name of Dr. Mario Linares Wilson, he lives now in Havana. He always insisted in promoting cultural activities in the societies. In one of those activities I got to know Nicolas Guillen in person. He was here in Guantánamo.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

In what year was that?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

In 1940. Nicolas Guillen was here in Guantánamo in the year 1940 and visited Club Moncada, La Nueva Era, and Siglo XX. As you may know, there were meetings and things. I can remember that there was a function in a theatre that was in front of…, yes, yes the name of the theatre was Teatro Blanco.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Teatro Blanco?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Blanco, because that was the name of the owner. And we did a function there, Nicolas Guillen also presented some of his poems.

You have to see how things were! In order for us to get that theatre, we had to guarantee everything by taking responsibility beforehand for the expenses. They charged us a price, I don’t remember how much right now. We had to pay everything, they did not take care of anything. It did not matter if people entered or not, we had to pay. But, everything worked out fine. Nicolas Guillen did a very good presentation of his poems. But, they, the owners, were reluctant because of the political positions of comrade Nicolas Guillen. They were afraid that after Nicolas Guillen left, that they would be boycotted.

All those things were happening then. (laughing)

So, you see that there were those people who at the same time were playing on the side of both God and the Devil.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Responding to the insistence of another guest who wants to join our dialogue, Agustín Manfarrol.

Come, come, come and let us hear your question. Agustín Manfarrol, President of the Association of Son “Lili Martinez Griñan here in Guantánamo. Just go ahead.

AGUSTIN MANFARROL:

I would like to hear you speak on the ‘asaltos’, ‘assaults’, that you used to keep in the societies. Besides, of the parties and dances you used to organize, please tell us also about the ‘asaltos’.

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Indeed, we used to speak of ‘asaltos’. That was when a member of the society had his or her birthday, then we came together and ‘assaulted’, as it were, his house and shared joy with the family. Of course, the family used to like that and enjoyed it a lot. It was very pleasant then. Because there were families where especially the wife, for reasons such as, for example, work, was not able to dedicate much time to do the same things we could do with collective effort. Yet, we the friends of the husband would arrive and for them that was something very important. They would offer us tea, refreshments or anything they had. It did not matter at all what they had. It was not necessary to have anything exquisite, but whatever they could afford was alright. Sometimes, when it was possible, we had a strong drink as a toast.

Other ‘asaltos’ were done in one another quarter where there were social institutions. We took music equipment and music, we danced and entertained the people of that particular neighborhood. I can still remember those record players that you had to spin by hand for them to play. (laughter).

EUGENE GODFRIED:

What other interesting stories could you tell us, as you consult your memory? Just like the story on the ‘asaltos’ that you just told us about? As a matter of fact that was a very interesting episode, what else did you do?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Well, I can remember the time that the processes of converting the clubs of people of color into official societies. That was the process of making their constitutions. A convention was held of the societies of blacks, as it was called over there in Havana. We had the opportunity to assist at that convention as President of our society. I can remember the first one we attended to was at the club Atenas in Havana.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Club Atenas was a similar one?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

A similar club, but it was considered a society of a higher rank among the societies of color in Havana. We could call that the most distinguished society. People of more level, the politicians of those times…

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Do I understand that a significant number of the politicians of African descent of those days came out of the Club Atenas?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

From Club Atenas and the different societies as well. For example, here in Guantánam,o there were a series of friends, who succeeded to become representatives. There was that one who was a dentist. What was his name again…, yes, Chivas. He managed to become a representative. And so there were many. Like the one who was a Mayor. His name was Hildelisu.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Hildelisu? And he became a Mayor of Guantánamo?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Hildelisu Olivares Especk, a black mayor. It was possible thanks to the support of the black societies to which he belong. Although he got the support of the wider community of the city, but most of his followers were blacks, mulattos, and people of color. So, he became Mayor and was in office for a long time, almost until the triumph of the revolution.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

So, was he a Mayor in the fifties?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

No, he started in the decade of the forties. He was a member of the political party known as ‘Partido Auténtico’.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

In those days you had three major political parties, am I right? Auténtico, Liberal, and Conservador?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Yes, you had Authéntico, Liberal, Conservador, you had also Popular, and the Ortodoxo, which was a split from the Auténtico. Most of them (blacks) joined the Orthodoxo. The Auténticos Radicales formed the Ortodoxo Party, which was very strong here in Guantánamo. “To sweep with Chivas” “Shame against money.” That was the slogan of that party. The Orthodox party was very strong here.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Good, good, good, You mentioned the stage of the triumph of the revolution. Before entering into that part, is there anything else remaining that had a strong impact that you still want to say? Let us say, things that are related to the presence and functioningof the societies of color.

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO ==>

vibrantly narrating his experience as Past

President of the Societies of people of African

descent in his home town, Guantánamo.

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Yes, let me tell you that really, independently of the economic situation and the buying potential of the black man, generally speaking, the black man always had his value here. His position was very well respected. There were many friends, who according to their possibilities and their characteristics, were always very well recognized, respected and considered. And because of that fact, it had its repercussions on the societies. It was not a matter of….of course there was always something, like you also have it now. But, the black man always had his value and was always respected. There was always something that proves that the black man was always looking to raise his educational level. It’s clear that it was not all that easy, one had to make a lot of effort. There was a typical case of a friend who had to make lots of efforts to educate himself. That’s how those things used to happen then.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Fine, let’s us continue to remember.

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

(Laughing) I am trying to, but it is difficult, it has been so many years now.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

I know, I know, but don’t you worry, because I have also to make lots of efforts in remembering, by going back, back, back in time. But we have to do that, otherwise the youth, many people and ourselves won’t be able to understand anything that is happening today in the world, if we don’t consult our memory.

You told us at the beginning of this dialogue that you took the example of your father, who was the founder of the first societies of color. Now you were saying that the black man demanded respect, his position, and he demanded what belonged to him. It seems to me that all of that was possible because the black man came walking down a long way through his struggles. Look at the names of those societies. One was called Aponte, over there in Santiago de Cuba, Moncada in Guantánamo. All were names of black freedom fighters. Aponte led the Rebellion of enslaved Africans in Cuba. Moncada was a fighter for the independence. La Nueva Era and Siglo XX, and all those names reflected hope for a better future. It would not surprise me that there might have existed one another society of color bearing the names of other leaders of the independence movement who were of color, like Antonio Maceo or Quintín Banderas.

But, fine. It seems to me that your father must have told you about the struggles led by the blacks over here in Guantánamo, La Maya and Santiago de Cuba. Those struggles waged by the blacks were to secure their survival and to demand their just place. Those endeavours even ended up in a big upheaval in the year 1912 and the massacre of the followers of the ‘Partido Independiente de Color’, the Independent Colored People’s Party. And, I think that we should never forget the existence of that party.

You were born after the days of those occurrences, but what can you remember of what your father and other friends could have told you about that epoch?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Yes, as you already know, in that epoch I was very young. But one can say that my father was a man of the people. Not because he was my father, but because he was an organizer of the masses. People of our descent really rallied around him.

He had a carpenter’s workshop in Santiago de Cuba, and there is still a signboard with his name saying, “DURRUTY”. On Sundays and Saturdays in the afternoon people gathered in that place with him. There is something I must say, that is, that the Blacks in Santiago, one had to take them very well into account. From that place [the carpenter’s workshop] conditions were prepared. And, I always remember their struggle to get a building to lodge the Club Aponte, which up to then didn’t have a seat. That was a firm battle, and as I told you there were people of weight who met there with him. It was a terrible battle. I always remember Dr. Amerigo Portuondo. The other Portuondos who were always present.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Our friend Agustin Manfarrol is asking permission to raise a question. Yes, please go ahead Agustin.

AGUSTIN MANFARROL:

Eugene, I want to ask Luis Durruty something, especially when he spoke about the Club Aponte, and he said that there was a battle for the headquarters. I would want Luis to speak more about what he mentioned on many occasions as the ‘level’ of the people. I think that when he mentions the word ‘level,’ that he is referring to the economic level or position of the members. Especially, that was the case with the Club La Nueva Era, its members, the Blacks, were not of high economic level. Their economic level was not so well as he indicated. Now, I would want him to explain to us, how did those members [of La Nueva Era in Guantánamo] get their location and who paid for the expenses.

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

That was terrible, very hard. There were some members who had a little better economic position, who worked at the railway, the sugar estates, the U.S. Naval Base, and they cooperated by putting money together to pay for the building. The owners who were white, always tried to get us drowned, that was a reality. So what happened was that at month’s end they were promptly on top of the leaders of the societies, looking for their payment. It was not really a lot of money, 20 or 25 pesos monthly. But still we had to struggle to get that money together in order to pay the rent. We had to remind the members that they should pay their contribution to pay for the rent, water and other expenses of the society.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Agustín wants to raise another question. Please feel free, Agustín.

AGUSTIN MANFARROL:

Luis, before anything I want to tell Eugene that you were the first President of the Society “Viejos amigos del Son Lili Martinez Griñan”. Luis was a very close friend of Lili Martinez Griñan. The name of the Society was from a proposal of Luis Durruty Nolasco.

I would like you to also speak about how the idea came up to work for the Son, and how the development has gone up to now.

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

That is very important. After some time of ‘the process’, almost all of the societies, for one reason or the other, started to close their doors.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

In what year more or less did that process of closing down of the societies started?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Now, after the triumph of the Revolution.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

The years 1960. 1961?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Yes during the years 1960, 1961 almost all of the societies closed their doors and stopped their activities. In those times the battle was directed to support of the triumph of the revolution. In reality we did not devote our time to those activities, on the contrary, we joint the battles on the guideliness we were receiving from our government, the revolutionary government. That, in my way of saying it, was partly one of the reasons why the societies declined and many of them were closed.

As the revolution was gaining strength, it became undoubtedly necessary to try to organize activities for the upcoming youths. The new generations of young people that was coming up should be permitted to recreate themselves. And, things had to take up their rhythm as before. We started to dedicate ourselves to that objective. As far as we the elder are concerned, we are still full of desire up to today, and we would be very glad if that could be maintained. We always liked that and we always gave the best of our effort to support that purpose.

So, we used to meet in the Marti Park, in the city of Guantánamo. Almost every day we had conversations among us, Manfarrol, Marco Obdulio Barton, a group of friends. We used to meet every afternoon and evening, but now we did not have a place anymore.

Then we decided that we had to organize a group, at least for us to talk, have a drink and recreate ourselves. That’s how the idea came up to found the group “Viejos Amigos del Son”.

So we met at the house of Gonado Horrero, may he rest in peace, who used to live in Avenida between Carlos Manuel de Cespedes and Luz Caballeros. We met there on Sundays. We held many meetings and we brought our snacks and drinks and we talked together until we finally concluded that the organization had to be founded. I was honored to become the President and Manfarrol the Vice President. There were others also like Mario Obdulio Barton and Collantes who died.

The need became urgent to have a location so we could take our wives too. Until we found a place at Cuca’s, who lived at Luz Caballeros. She moved to Havana and offered us to use her house, which remained empty. She told me, yes, Luisito you could go ahead and organize your meetings and activities. That’s how we initiated again the question of the ‘Viejos Amigos del Son’.

By the time we were making the regulations, I suggested to name it Lili Martinez Griñan. He was a musician who had been very successfull here. He never refused to play for us because of payment. Whenever he was asked to play and there were no conditions to pay, he would say no problem, and would take all of his musicians with him to play with no payment on a Sunday.

Up to now we are struggling. You see, I am here but I am still remembering the problems of our group. I always go to activities when possible, even though I cannot give the same contribution that the group needs. In reality I reached a stage in which I could not give the kind of support that the association ‘Viejos Amigos del Son’ needed and still needs. So, we asked the Board members permission to allow us to be replaced and not to occupy a space that someone with more energy could fill up. That is how it happened. Now, we have our friend Manfarrol as the President of the ‘Viejos Amigos del Son Lili Martinez Griñan’.

I want you to know that there was a struggle that was nothing easy. It was not easy to organize all of that. They gave us that building which was a garbage place. Full of garbage. We had to throw out cans and thrash to clean up. So as you can see we went through a whole process, not easy at all and the battle is tough. We are keeping on. My consideration is that there is interest, but not everything depends only on having interest. There is still a lot to happen in order to build up the association.

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO

EMMINENT BLACK ACTIVIST AND

A DEEP THINKER IN DIALOGUE…

EUGENE GODFRIED:

‘Viejos Amigos del Son’, fine we are talking about history. And when we talk about history we talk with rigidity. That means to say that if we were to take matters into account we could not be complacent with anyone, otherwise we would not reach what we want, right? That is, that the association ‘Viejos Amigos del Son’ should occupy the place it deserves. Because, it is the people’s legacy. And it is the result of quite a long struggle led by the people of African descent or of black, or coloreds, as they would like to call us. Yes, ‘Viejos Amigos del Son’, meaning in the English language: ‘Old friends of the Son’. It makes me think that we are - old friends - of the clubs Moncada, La Nueva Era, Siglo XX, am I right?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Completely!

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Because, Lili Martinez worked with them. And he became a big personality of music through his work with them.

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

That was the band of the societies of the blacks.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Exactly, Agustín please come closer, don’t sit so far away from us. Come and join us.

Agustín took over the leadership from you, you took over before that from your father. We have Luis Bennett Robinson also here with us helping as a photographer and sound engineer, he and his children will have to take over from us to carry on with this struggle which should forever be invincible. Is that so?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Completamente! Completely! That is fundamental!

EUGENIO GODFRIED:

Your location, it seems to me that we reached the year 1961, I am reflecting, and I don’t know why I am reflecting, but I feel that I have to be making reflexions.

In 1961 it was decided upon for x y z reasons, that the revolution arrived and we had to strengthen that process. Yes, we Blacks had to gave way so that the revolution could be strengthened. Fine, thank you very much!! But, I hear up to today that even in Havana that there still are associations of Galicians, Andalucians, and of all the regional representations in Spain.

But, we the blacks had to make way and dismantle our societies. We are currently still striving to convert a garbage place into a headquarter for us. Am I right or am I saying incorrect things?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

You are completely right. Besides, our objective has always been that. We have really struggled until now. We haven’t reached yet, but our objective is to always move up higher. And that’s what we are doing.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Agustín wants to say something.

AGUSTIN MANFAROL

Luis, in this brave interview that Eugene is doing with you today, you touched some points, I wish you could further speak on them. Firstly, that your father was one of the leading figures of the societies of color, as we usually call them. And, when you moved to Guantánamo, you also formed part of La Nueva Era and Moncada. As you said Moncada nurtured itself from La Nueva Era, because it was the society color of the youths, who did not have much economic potential. That’s the reason why.

You touched a point, and I would want you to answer me. I am the son of Abram Cuesta, a brother of Amado Cuesta, who was also your brother. I don’t know if you remember whether my father was related to your father? Because, when my father went to Camaguey, he founded a society of color there named Union Club.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Union Club, and in what year was that?

AGUSTIN MANFARROL:

In the years 1936 to 1940.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

In Camaguey. Nuevitas, Camaguey?

AGUSTIN MANFARROL:

Yes, Nuevitas in Camaguey.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Luis, the floor is yours.

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

During those times, precisely, my father was blossoming in the activities of those societies. And he participated in many meetings in Havana. I still have invitation cards somewhere with me. You can be sure of one thing that Abram Cuesta was a very close friend of my father. And in those times my father maintained close friendly relations with your father Abram Cuesta, your father. Because, I want to tell you something more. On one occasions when I went to Havana for one of those meetings, I also met with a brother of Nicolas Guillen, Batista.

Resources were low, economic resources then. Just the other day I was talking to my wife here, I was telling her about the place where all of us leaders of the societies were lodged. In that house a sister of Robilio Urbe was living, who moved to Havana. She arranged for us to stay at that house. That’s where I met with a brother of Nicolas Guillen. His second surname was Batista.

They, the leaders of the Black Societies, met there. I was younger and I know that on that occasion Abram Cuesta was also there. I may not remember his face now, but I can remember clearly that as the meeting went on someone would ask: “Hey Abram what do you think of that?” The conversations went around several topics. You had representations of Oriente, Camaguey, Matanzas.

Oh, there are so many things to say, and that one slipped away from my mind .You really took me by surprise, I could not even….(laughter), your brother Marito, Chanito, I was going to ask you for him, Agustin. That’s how things were.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Fine, I don’t want to have our guest Luis getting too weary. He has been so gentle and generous to share this microphone in this dialogue with friends of the whole world.

To speak some about the reality of the time of the societies of colored people or black people, up until the transformations into the association “Viejos Amigos del Son”, meaning Old friends of Son, friends who will never become old, isn’t that so?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Yes, yes (laughter)

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Is that right?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Completely,

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Always young, because we will always continue to struggle for the wellbeing of our people and for the SON.

I don’t know if there is anything else left that you want to still say from the bottom of your heart?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

No, my friend, I must say that I was pleasantly surprised by your visit. I could have gathered more information to share with you. But, on another occasion I am at your disposal whenever you consider necessary to do so. We can share views we were always interested to see that those struggles become known. Because, we always struggled. The blacks have really struggled, with a lot of strength. Struggling always for us to be respected and considered. That’s fundamental. That’s fundamental, before, now, and after.

AGUSTIN MANFARROL:

Excuse me Luis, just to add something, always struggling for our space in the wider communtiy.

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Above all, above all, precisely, that is where the fundamental point lies.

Well my friend, Eugene, you see here you have my small home, it’s at your service whenever you need. Here I am with my wife, already old as we are, but always interested to see that there is progress and that those ideas could be maintained for the well – being of all. Because, we the elder are in decay, but the youths are coming up and they need that kind of social support.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Clearly, a home which offered hospitality to us, that feeling of fraternity also, and we are very hopeful with all that information that you shared with us, Luis.

We wish you lots of good things, lots of good health. Strength and courage. Forward ever. And we will always keep our youthful spirit with which you have inspired us today. Marching always forward as we depart from your home. Speaking about your home, where is it located? Which is your adress?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Calle 1, West between 3 and 4 Sur. Guantánamo City.

House - number 1363.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

I said you were young, what is your age?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Eighty six (86), almost nothing. (laughter)

And here is my wife.

EUGENE GODFRIED

Hi, madame, what is her name?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Bertilia Wilson Wilson

EUGENIO GODFRIED:

Wilson Wilson, that sounds like a name from the anglophone area of the Caribbean.

<==

LUIS MARIANO DURRUTY NOLASCO <==

LUIS MARIANO DURRUTY NOLASCO

AND HIS WIFE BERTILIA WILSON WILSON

GUANTANAMO

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Well, our guests had the need to add a couple of very important information to our dialogue. We will be brief.

We have with us again our friend Agustín Manfarrol, who is the President of the association Viejos Amigos del Son Lili Martinez Griñan. And, also our respected guest the first President of that same organization. And who years before was active with the societies of Blacks here in Guantánamo. Luis…?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Hi again and I am Luis Mariano Durruty Nolasco.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Oh, what a brilliant voice. (laughter)

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

Thank you very much.

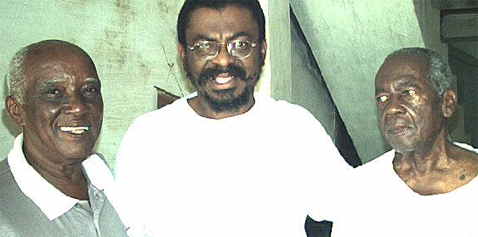

<== AGUSTIN MANFARROL (LEFT)

<== AGUSTIN MANFARROL (LEFT)

EUGENE GODFRIED (CENTER)

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO (RIGHT)

EUGENE GODFRIED:

(laughter) That came from the bottom of my heart.

Agustín and Luis, please tell us both of you, the Presidents of the societies La Nueva Era and Moncada and if you could also remember the society of mulattos, Siglo XX, who were their Presidents at the time of the triumph of the revolution during the first years?

AGUSTIN MANFARROL:

Yes, the Presidents of La Nueva Era and Moncada, those societies we had relations with, were, Atanacio Chivas for La Nueva Era and Xenobio Mustelier for Moncada.

At the moment of the triumph of the revolution, as Luis said, their was effervescence, we turned over and we participated in all the revolutionary activities. There was an impasse in the societies of color. During that impasse is when the transitions happened. We acquired the building through the Urban Reform! The locations were already ours. Thus, of the [Black] societies! And when I say ours, it is because we were big. So, then when that transition appeared then there was a stage in which those locations were handed over to the state. One was taken by the Construction Workers Trade Union and the other one was given to the Ministry of Education. We are researching how that transition took place. We will continue to do our research, Eugene, and we will let you know. Because, there was a time that we didn’t have any location. We tried to purchase them back, but they were already in the hands of those other organizations.

So, as Luis said, we took the initiative to arrange with Cuca, who offered us her house. We started in Cuca’s house.

There is another part of this story and I want to stress this, that when the anglophones of the British West Indian Welfare Center saw us without a place, they offered us their space. Because the Africans, and when I say Africans, I mean to say the Jamaican, Barbadians, Cubans, and all, with that sign of solidarity leant us their center. And they were so generous that they shared the time table for the use of their space with us. For example, if we used the building from Monday to Wednesday, then they would use it from Thursday to Friday. Saturdays and Sundays were also divided among our two organizations.

While being in the [British West Indian Welfare] Center, we got the current building that Luis said was a garbage place. They gave it to us and we started the struggle.

But we did not succeed in knowing how the transition really took place. The two Presidents and most of the members of the Board of both La Nueva Era and Moncada already died. But we want to find those documents too. We know that especially Moncada, or both, had a Board and a Secretariat which were very well organized. Very well organized. Luis Durruty was Secretary of La Nueva Era one time. I don’t know if….

CARIBBEAN CENTER -- PEACE EQUALITY & SOLIDARITY:

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Very clear, I don’t know whether you have something more to say, Luis?

LUIS DURRUTY NOLASCO:

No, we listened and our friend Manfarrol stated something that I didn’t keep in my mind right away, but they happened as he said. What I wanted to say is that it was like a paradox that location of La Nueva Era, I am going to look for some more friends who were around in that period, to see whether they can contribute with more information. But, look how life is. You see Telin, the son of Estaban Garvey. Well, the son of Esteban Garvey, who was then together with Pozo in the Housing Department, and through mediation of the CTC (Trade Union Council) sent for me and they handed me the keys of La Nueva Era. But, on that occasion for the Construction Workers Trade Union of which I was also the Secretary after the triumph of the revolution.

So that is how I received again the key of what was the society La Nueva Era. Look how many sides that problem has. That is why I will remember intensively, and I will look for the assistance of some friends who I am sure know more about your question with regards to the transition. It is really very important.

EUGENE GODFRIED:

Indeed, very important, very important, and it was a pleasure.

THE END

All Photos in this article © 2004 Luis Bennett

Robinson

|

![]() Mr.

Godfried recommends the following book related to this topic:

Mr.

Godfried recommends the following book related to this topic: