|

AfroCubaWeb

|

|

For an account the festival, see Cuban Abakua Participate in the Ekpe Festival, The Investiture of Lady Elizabeth Ayo Eremie into the Ekoretonko Lodge, Calabar, Nigeria, 9/05 |

|

|

|

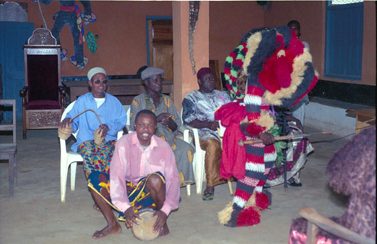

Ekpe Musicians, Calabar |

"The Cuban Abakuá society — derived from the Èfìk Ékpè and Ejagham Ngbè societies of southeastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroon — was founded in Havana in the 1830s by captured leaders of Cross River villages. . . . Abakuá intellectuals have used commercial recordings to extol their history and ritual lineages. Evidence indicates that Cuban Abakuá identity is based on detailed knowledge of ritual lineages stemming from specific locations in their homelands, and not upon a vague notion of an African “national” or “ethnic” identity. . . . After publication of samples of Abakuá phrases from a commercially recorded album (Miller 2000), Nigerian members of the Cross River Ékpè society living in the USA informed me that they had recognized these texts as part of their own history. Èfìk people in the USA had learned about the Cuban Abakuá and were actively searching for contact with its members. The

website www.efik.com (now defunct) had references to Cuban tourist literature on the Abakuá in Spanish; our communication led to what was perhaps the first meeting between both groups. The privilege of examining this material with both Cuban Abakuá and Èfìk Ékpè members has provoked me to grapple with questions of using oral history materials as new evidence for rethinking the African Diaspora in the Caribbean. A specific example can illustrate this interpretive process:![]()

|

|

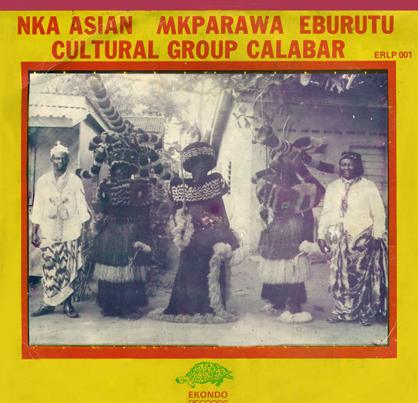

Title translates

as "group of young proud Efik." |

"Okobio Enyenisón, awana bekura mendo/ Núnkue Itia Ororo Kánde Efí Kebutón/ Oo Ékue”

This phrase is part of an Abakuá chant memorializing the actions of Èfìk and Efut leaders who helped found the society. Abakuá leaders interpret this phrase as: “Our African brothers, from the sacred place/ came to Havana, and in Regla founded Efík Ebutón/ we salute the Ékue drum.”

Mr. Orok Edem, an Èfìk scholar residing in the USA, equated “Efí Kebutón,” the name of Cuba’s first Abakuá group, with “Obutong,” an Èfìk town in the Cross River region. He interpreted many Abakuá terms as deriving from Àbàkpà, an Èfìk term for the Qua settlement in Calabar, originally formed by migrants from the Ejagham-speaking area to the north.

After connecting with Edem, I was invited to facilitate an exchange between a group of Cuban Abakuá and West African Ékpè at the Èfìk National Association meeting in New York in 2001. In preparation for this event, I introduced Asuquo Ukpong, an Èfìk Ékpè member, to several Abakuá musicians at a local cabaret performance. As they played, Ukpong enthusiastically identified many possible relationships to Èfìk culture in the form of dance and musical instruments. During an Abakuá chant, Asuquo danced towards the Cuban musicians; then as the lead drummer stepped forward, Asuquo gestured symbolically with his eyes and hands. A Cuban Abakuá dancer joined them, also using a vocabulary of gestures dense with symbolism. This was perhaps the first time that Ékpè and Abakuá members had met in a performance context, and their ability to communicate through movement contrasted with the divisions between them created by Spanish and English, their respective colonial languages.

A week later, a group of Abakuá attended the Èfìk National Association meeting. An ìdèm Ékpè

|

|

Ekpe Musicians in Oban, Cross River

State |

costume, visually very similar to that of the Cubans, danced to the accompaniment of a large ensemble of musicians and chanters. In the 1860s, Rev. Goldie translated this Èfìk term as: “Idem ...A representative of Egbo [Ékpè] who runs about the town.” Essien (1986: 9) reported Ídêm as ‘masquerade’ in Ìbìbìò.

As the Cubans prepared to perform, they realized that their Íreme — a term derived from Èfìk pronunciation of “ìdèm Efí” — costume lacked the ananyongá (ritual waist sash), as well as the nkaniká bells placed over it. In Èfìk, “Ñ-kan’-i-ka, n. 1. A bell . . . Nyeñe ñkanika, Ring the bell, by shaking it.” Lit. ‘shake bell.’![]()

|

|

"Obane Sese Condo" - an

Abakua |

They explained that an Íreme cannot function without these, together with herbs and a staff in the hands. As Ékpè masquerades are nearly identical to those of Abakuá, these items could be lent by the Èfìk. This interchange of ritual objects occurred in a matter-of-fact fashion, a further indication of cultural similarity between the two areas.

Similar use of nkaniká ‘bells’ was recorded on both sides of the Atlantic. While in the Cross River region in 1847, Rev. H.M. Waddell

described two Ékpè masked dancers wearing bells: “Two Egbo [Ékpè] runners in their harlequin costume entered the town to clear the streets. Their bells, dangling at their waists, gave notice of their approach.” In the streets of Havana, a late nineteenth century description of the Three King’s Day processions notes the Abakuá “covered in coarse hoods . . . so large and bulky that to their sides arms and

legs appeared like simple appendages. . . . they marched slowly . . . behind the dancers, who did not cease, in their startling convulsions, from shaking the many bells they carried bound to their waists” (Meza

1891)."

|

|

The title "Ubane" refers

to Obane, |

|

|

Ekpe celebration in Calabar, 9/04 |

For an account the festival, see Cuban Abakua Participate in the Ekpe Festival,

December 19-26, 2004, Cross River State, Nigeria

See also our Abakua page.

[AfroCubaWeb] [Site Map] [Music] [Arts] [Authors] [News] [Search this site]